AI has long been integral to many assistive technologies, and we have seen over the course of this year that there is considerable exploration occurring around the use of generative AI to enhance accessibility in education. In this post we look at a few of the emerging uses we’ve seen as well as discussing some of the key concerns and challenges arising.

Personalising content

Personalisation is often highlighted as a key area in which AI can enhance accessibility for students. This is often discussed in relation to intelligent tutoring systems (ITS) which typically look to provide custom pathways through content for students which are specific to their needs. Over the past year though the sudden availability of AI text generation looks to be bringing new and different opportunities for students and staff to change and customise content.

While AI text generators can create brand-new text, they can also be particularly effective at reworking existing text. This has opened a wide range of possibilities for users to use these tools to rework content based on their individual needs and preferences.

This might include:

- Translating the language

- Simplifying

- Reformatting – adding paragraphs, punctuation

- Rephrasing

- Providing analogies/examples

- Explaining

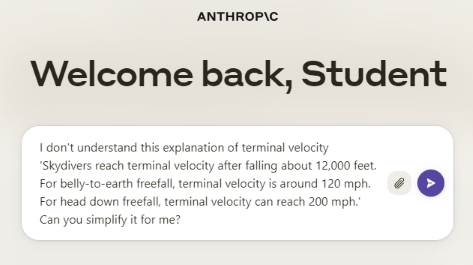

For example, below is an actual conversation with Anthropic’s Claude chatbot demonstrating how a student might ask for clarification on an example given to them, and then generate further examples to aid their understanding:

Student:

I don’t understand this explanation of terminal velocity ‘Skydivers reach terminal velocity after falling about 12,000 feet. For belly-to-earth freefall, terminal velocity is around 120 mph. For head down freefall, terminal velocity can reach 200 mph.’ Can you simplify it for me?Claude:

Here is a simplified explanation of terminal velocity:Terminal velocity is the maximum speed something can fall. When skydiving, jumpers accelerate as they fall, but air resistance increases the faster they go. Eventually the air resistance equals the force of gravity pulling them down. At this point they stop accelerating and reach terminal velocity.

For a belly-to-earth freefall position, terminal velocity is around 120 mph. This is because the skydiver’s body has more surface area for air resistance in this position.

For a head down freefall position, terminal velocity can reach up to 200 mph. This is because the skydiver’s body is more streamlined in this position, creating less air resistance.

It takes about 12,000 feet of falling for skydivers to reach terminal velocity. Once they reach it, they stop accelerating and fall at a stable maximum speed the rest of the way.

Student:

Can you give me more examples of terminal velocity?Claude:

Here are some more examples of terminal velocity:– Raindrops reach a terminal velocity of around 9-10 m/s (20-22 mph). Their small size and low mass means they accelerate quickly but also have little air resistance.

– Hailstones can reach faster terminal velocities of around 20 m/s (45 mph). They are larger than raindrops and so accelerate faster and encounter more air resistance.

– Falcons diving for prey can reach terminal velocities over 320 km/h (200 mph). Their streamlined bodies and swept-back wings help minimize drag.

– Spacecraft like shuttles have very high terminal velocities when re-entering the atmosphere, over 1,700 m/s (3,800 mph). The extreme speeds generate enormous drag that slows the craft.

So in summary, an object’s mass, surface area, aerodynamics and the density of the fluid it is falling through all affect the terminal velocity.

Students can input course content they need help with and prompt the text generator to rework it as needed. In this situation, they can rework the content independently of their teacher and ask for as many iterations as they need. These AI tools are infinitely patient and non-judgmental as well as being available 24/7 – key factors which make them an accessible and attractive option to students.

Liss Chard-Hall, who has provided several informative sessions around using generative AI with neurodivergent students, has outlined how students might use these techniques not only for course content but also for navigating the often-confusing language of academia. For instance, asking ChatGPT to explain a course objective or learning outcome in plain language.

Students might use chatbot style services like ChatGPT, Bing Chat, and Google Bard to perform these tasks. For students not as comfortable with prompting the AI directly though there are tools emerging which provide easier access by crafting the prompt for them. goblin.tools is a great example of this and it has been built specifically for neurodivergent users. This platform uses generative AI to offer a range of tools to help neurodivergent users with tasks they may struggle with, including estimating the tone of text, changing the tone of their own writing and estimating how long a given task might take to complete.

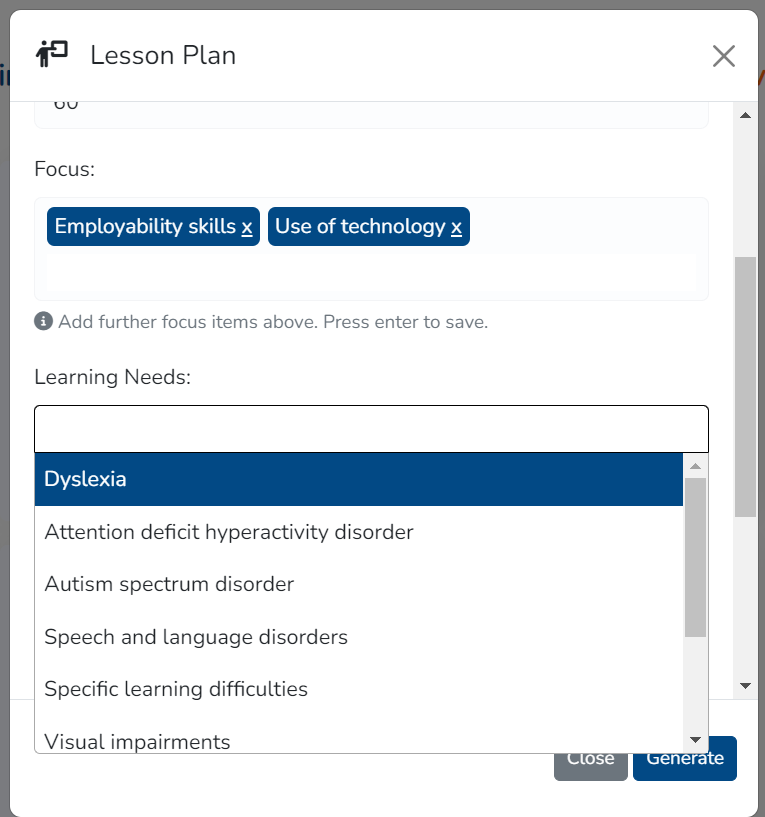

Teaching staff can also make use of these techniques to customise content for their students. TeacherMatic, which provides a series of content generators for teachers, has added a ‘Learning Needs’ specifier to their lesson plan generator which, in a similar way to goblin.tools, helps the user by customising their prompt for them to get an output suited for a particular task.

These tools may also be helpful in improving the accessibility of documents. Ben Brumfield presents an interesting case using ChatGPT to change the spelling and grammar in historic texts so that they can be more easily read by a screen reader. They do note that there are still issues with the way ChatGPT handled the text – it had misinterpreted the meaning of some words and even replaced others it found problematic.

AI collaborators

This year we have seen a lot of existing providers expanding their offerings using generative AI. Notably many are positioning their new functionality as a sort of AI collaborator – an assistant which works with the user providing one on one support for writing, coding and more. Tools like Grammarly and Quillbot for instance now offer far more than grammar checking and cover more comprehensive writing assistance including supporting users with generating ideas, improving formatting and adjusting tone.

These enhanced tools could provide considerable benefit to disabled users. For example, Anton Mirhorodchenko, a software developer with cerebral palsy, explains how GitHub Copilot, which supports users with coding suggestions and advice, has improved his experience as it “simplifies the physical acts of coding and writing”. Anton provides the AI Copilot with a shorthand version of the code he wants to write and it can expand this automatically, reducing a considerable amount of the typing required. He has produced a free guide for using generative AI for software development which explains his process further.

Microsoft’s Copilot, which will be released soon as part of a free update to Windows 11, similarly intends to be an ‘everyday AI companion’ and will sit within a wide array of Microsoft tools including the Office suite, Edge browser and many apps. Google too has recently expanded the reach of Bard which will be able to support users across users Google docs, email, maps and more.

It looks like in the relatively near future these AI collaborators will be commonplace features in a lot of the software we use regularly. This could be a benefit for accessibility, providing easier access to these tools for all users and standardising this level of support in a similar way spell checking tools have become a commonplace feature.

Concerns

These are emerging uses of a still quite new technology and though there are clearly opportunities for using generative tools to enhance accessibility there are notable concerns too. Liss Chard-Hill raises the key point that “AI is not a neurodivergent thinker” – the data that these models are trained on is primarily from neurotypical writing, so their outputs are going to follow in that style. There is concern therefore that promoting the use of generative AI to adjust tone and writing style could encourage students to homogenise their communication, erasing their own unique voice and creativity in favour of a standardised, neurotypical one.

With many students being interested in, and actively using, all kinds of generative AI there is also the question of how accessible these popular tools are themselves. In this year’s AI in tertiary education report we explored the financial cost of subscriptions to the most popular generative tools. Digital inequality is a key issue and users who can afford to pay for these services will have access to more advanced features and capabilities than those who can’t.

There remains too the issue of hallucinations, a text generator could well provide an example or analogy which is not applicable or a summary which misses key points. Students cannot rely fully on these services to explore their course content. Further, the availability of this technology should never be used as an excuse to not provide students with the necessary accommodations for their needs. For instance, the burden shouldn’t be on students to change the format of their course content so that it is accessible, it remains on institutions to provide accessible documents.

Generative AI though can potentially make creating those accessible materials easier for the educator and provide more options to disabled students. We are keen to explore this developing area further in this new academic year and would like to hear from members about their experiences. Please get in touch to AI@jisc.ac.uk if you are exploring this area and are interested in sharing your experience.

Check out the Accessibility community group for support and guidance around accessibility.

Find out more by visiting our Artificial Intelligence page to view publications and resources, join us for events and discover what AI has to offer through our range of interactive online demos.

For regular updates from the team sign up to our mailing list.

Get in touch with the team directly at AI@jisc.ac.uk