Publishing an intro to generative AI is a challenge as things are moving so quickly. However, we think things have now settled down enough for us to bring together information in a single place, to create a short primer. This blog post will be updated as needed, and we have also produced a version as a more formal report.

Version 1.6– 14th Aug 2024. First version published in April 2023.

Table of Contents

2. An Introduction to the Generative AI Technology

2.6 Image and Video Generation

3. Impact of Generative AI on Education

3.1.1 Guidance on advice to students

3.1.2 The role of AI detectors

3.2 Use in Learning and Teaching

3.2.1 Examples of use by students

3.2.2 Examples of use by teaching staff

3.2.3 Examples of uses to avoid

3.3 Adapting curriculum to reflect the use of AI in work and society.

1. Introduction

Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT are already having a significant impact on education. These tools pose considerable challenges around assessment and academic integrity, but also present opportunities, for example saving staff time by helping with the creation of learning materials or presenting students with new tools to enhance the way they work. The impact of generative AI is being felt far beyond education, and it is already starting to change the way we work. This presents more challenges and opportunities, in making sure education prepares students for an AI-augmented workplace, and that assessments are authentic yet robust.

The primer is intended as a short introduction to generative AI, exploring some of the main points and areas relevant to education, including two main elements:

- An introduction to Generative AI technology

- The implications of Generative AI on education

2. An Introduction to the Generative AI Technology

| Key Points |

|

Whilst we do not need a detailed technical understanding of the technology to make use of it, some understanding helps us understand its strengths, weaknesses, and issues to consider. In this section, we will be looking into the technology in a little more detail.

This is a fast-moving space, and the information here is likely to age quickly! This edition was updated in August 2024, and we aim to update it regularly to take into account significant developments.

This guide starts by looking at AI text generators, also known as Large Language Models (LLMs).

2.1 ChatGPT

ChatGPT has grabbed most of the headlines since its launch in November 2022. It was created by a company called OpenAI, which started as a not-for-profit research organisation (hence the name) but is now a fully commercial company with heavy investment from Microsoft. It is available as a free version, plus a premium version at $20 a month, which provides more reliable access, as well as access to its latest features.

ChatGPT is based on a machine learning approach called ‘Transformers’, first proposed in 2017, and is pre-trained on large chunks of the internet, which gives it the ability to generate text in response to user prompts, hence the name ‘Generative Pre-trained Transformer’. Whilst OpenAI provided some information on the approach for training ChatGPT, they haven’t so far, released any information about GPT-4o, the latest model released in 2024.

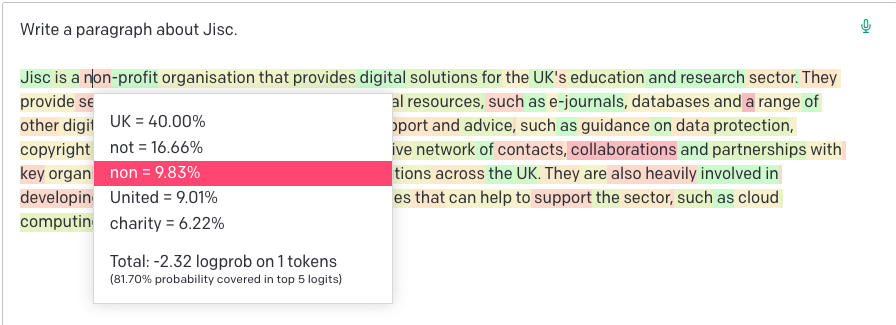

In its basic form, ChatGPT works by predicting the next word given a sequence of words. This is important to understand, as in this mode, it is not in any sense understanding your question and then searching for a result and has no concept of whether the text it is producing is correct. This leads it to be prone to producing plausible untruths or, as they are often known, hallucinations.

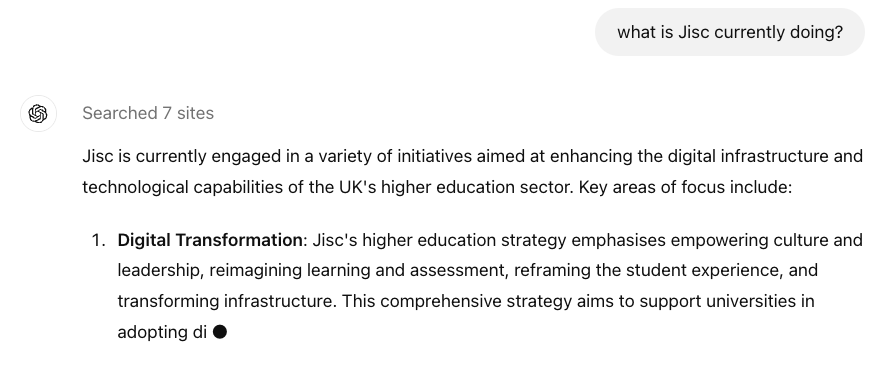

Both the free and paid versions of ChatGPT have access to the internet, and depending on the question, it will search the internet for the answer. When it does this, it will be clear this is happening in the user interface. Below you can see it saying it has searched seven sites. In this mode, ChatGPT will use the power of large language models to summarise the information on the websites and compose an answer. Even in this mode, we will still see inaccurate information or ‘hallucinations’.

ChatGPT Plus customers also have the ability to create GPTs which extend ChatGPT’s functionality. This is replacing an earlier tool called ‘Plugins’, and allows any user to create a custom version of ChatGPT, focused on a particular task. Any ChatGPT user can use a GPT.

In addition, ChatGPT can read documents and images, and can also create images.

OpenAI makes its service available to other developers, so many other applications make use of it, including many writing tools such as Jasper and Writesonic, as well as chatbots in popular applications such as Snapchat.

2.2. Microsoft’s Copilot tools

Although ChatGPT has got most of the hype, there are other players in this space, and this number is likely to increase. Microsoft have several products, all based on OpenAI’s technology, and variations of the name ‘Copilot’.

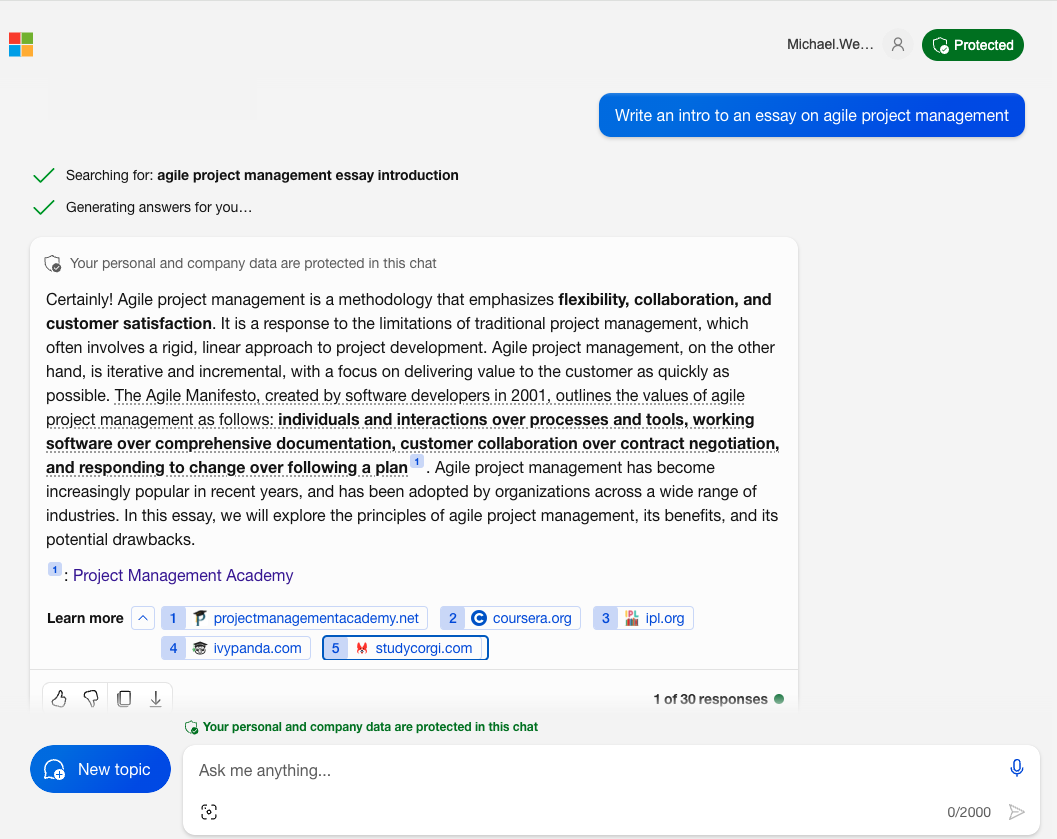

Of most interest to education at the moment is Microsoft Copilot (which was called Bing Chat), which is based on Open AI’s GPT-4. It’s a chat tool focused on searching for information and does have access to the internet. It takes your question, performs one or more web searches based on your question, and will then attempt to summarise and answer, giving references for the sites it uses.

There is also an enterprise edition – this version is likely to be highly attractive to universities and colleges, as it ensures data and information included in the chats isn’t used for training.

Microsoft has also introduced Microsoft Copilot for 365 – a set of generative AI tools for Microsoft 365 (i.e. Word, Excel, PowerPoint etc). These cost $30 a month per user.

These tools, along with a similar set from Google, move generative AI from a separate concern to part of ‘everyday AI’ – tools our staff and students use every day.

2.3 Google’s Gemini

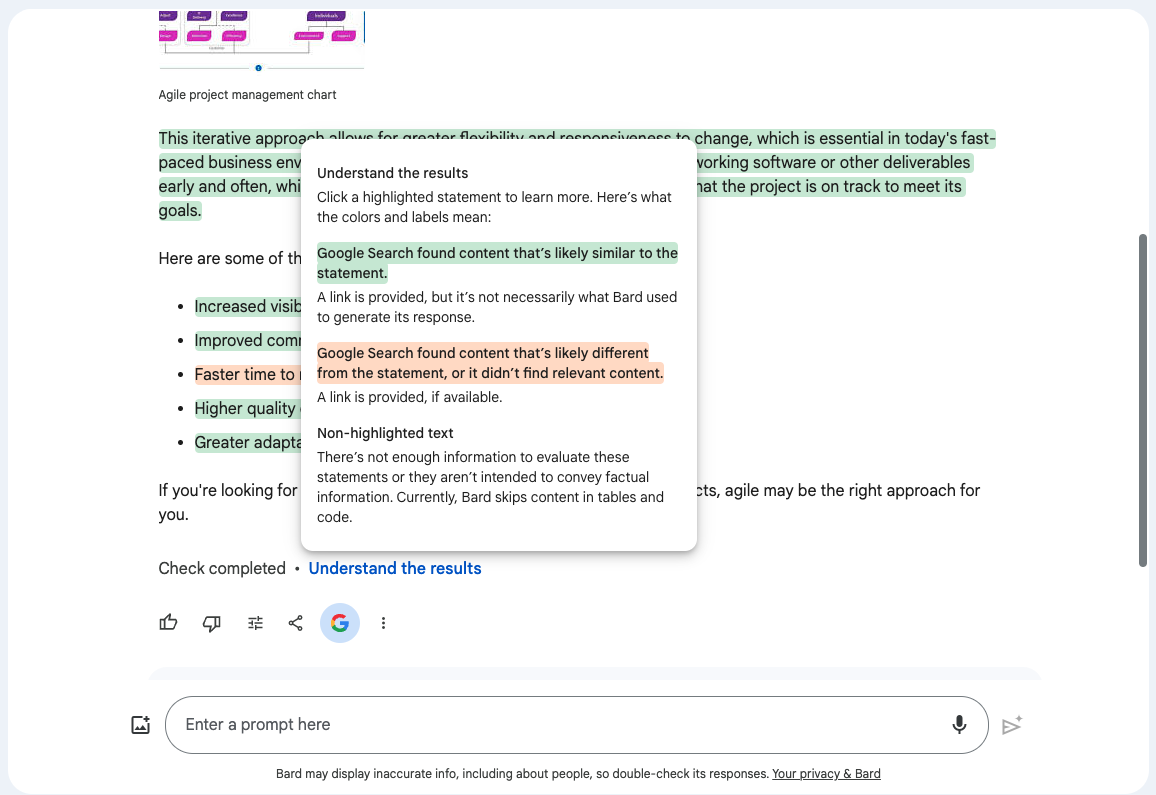

Gemini is Google’s equivalent of Microsoft Copilot, and is powered by Google’s own AI models. It was previous known as Bard. Like Copilot, it can access the internet, but unlike Copilot, it doesn’t provide references for the sites it used to give its answers, at least in its initial response. It does however have an interesting ‘fact-checking’ feature, where it will search the web for similar content to back up its answers and show you where it found the information.

Gemini is available in two flavours – a basic version, similar to the free version of ChatGPT in terms of capability, and a paid version, costing £18.99 a month, and similar to ChatGPT Plus in terms of capability, with the additional advantage of integration into Google Docs in a similar way to the paid Copilot 365 and Microsoft Word.

2.4 Other models

There are quite a few other models under development – Claude and Llama being two of the more notable.

Claude is similar to ChatGPT and is produced by Anthropic. It is likely to be built into many applications going forward.

Meta’s Llama is slightly different in that it has been made available as an open-source model, meaning that you can run it yourself. Open-source AI models often differ from open-source software though, and it’s not possible to fully understand how the Llama model works, or modify it yourself, from this release.

2.5. A summary of key capabilities, limitations, and concerns around ChatGPT and other Large Language Models.

In considering generative AI, it’s important not only to understand its capabilities but also its limitations. We also believe users should have a broader understanding of the societal impact of generative AI. Some of the key themes are summarised here:

| Capabilities | Limitations | Concerns |

|

|

|

2.6 Image and Video Generation

It’s not all about text – image generation tools have made huge progress too, particularly with Midjourney, DALL-E and Stable Diffusion.

These work in a similar way to text generators – the user gives a prompt and one or more variations of images are produced.

Video generation tools are also moving to mainstream use, including tools from RunwayML and Pika. These tools can current create short videos, typically a few seconds, from either a text prompt or a prompt and still image. OpenAI have announced another tool – Sora, which is current only available to selected users, but has very impressive demo videos.

As for the text generators, these have been trained on information scraped from the internet, and there is a lot of concern about the copyright of the training material.

Image generation capabilities are being incorporated into general AI services, so Microsoft Copilot, for example, can also generate images, using OpenAI’s DALL-E.

2.7 Beyond Chatbots

Whilst the focus has been on chatbots and image generation, generative AI is finding its way into a wide range of tools and services that can potentially be used in education. As an example, Teachermatic can create a range of resources for teachers, including lesson plans and quizzes, Gamma can create websites and presentations, and Curipod can create interactive learning resources. Many of these applications are built on tools provided by OpenAI and powered by the same technology as ChatGPT.

3. Impact of Generative AI on Education

| Key Points |

|

The impact of generative AI in education is still unfolding and is likely to for some time to come. Key areas include assessment and academic integrity, its use in teaching and learning, use as a time-saving tool, and use by students.

Jisc has convened a number of working groups with representatives from universities and colleges to help us collate and present more detailed advice in these areas, particularly around sector-level advice, assessment and advice to students. One of the first outputs of this work – Assessment Menu: Designing assessment in an AI enabled world – is now available.

Here we will now give an overview of the core themes.

3.1 Assessment

Initial discussions about generative AI have focused on assessment, with the concern that students will use generative AI to write essays or answer other assignments. This has parallels with concerns around essay mills. These concerns are valid, and whilst essays produced wholly by generative AI are unlikely to get the highest marks, their capability is improving all the time. The ability isn’t just limited to essays. ChatGPT is also highly capable of answering multiple-choice questions and will attempt most forms of shorter-form questions. It will often fall short, especially when answers are highly mathematical, although this will not be obvious to the student using the chatbot service.

There are three main options, each with their own challenges. There is broad acceptance that ‘embrace and adapt’ is the best strategy in most instances.

| Strategy | Approach | Challenges |

| Avoid | Revert to in-person exams where the use of AI isn’t possible | This moves away from authentic assessment and creates many logistical challenges. |

| Outrun | Devise an assessment that AI can’t do. | AI is advancing rapidly and given the time between the assessment being set and it being taken, AI might well be able to do the assignment when it is taken. |

| Embrace and adapt | Embrace the use of AI, discuss the appropriate use of AI with students, and actively encourage its use to create authentic assessments | Balancing authentic assessment and the use of generative AI with academic integrity is a challenge. |

The immediate action is for all staff to engage with generative AI and try it themselves, learning how their assessments will be impacted. Alongside this, institutions will need to consider their strategic approach to AI, review, and update policies, and communicate guidance to students.

For higher education, this aligns with guidance provided by QAA, and for both higher education and further education, general guidance has been provided by the Department for Education. In addition, the Joint Council for Qualifications has produced guidance for protecting quality of qualifications.

3.1.1 Guidance on advice to students

We are seeing the guidance to students being published by many institutions. Getting the wording on this can be challenging, and is discussed further in a Jisc blog post ‘Considerations on wording when creating advice or policy on AI use’. Our key messages are:

- Don’t try to ‘ban’ specific technology or AI as a whole.

- Describe acceptable and expected behaviours and provide examples.

- The detail of advice will vary between subjects, so supplement general advice with tailored advice for the subject.

We have produced an example of guidance for students, aimed particularly at colleges.

3.1.2 The role of AI detectors

Discussions about academic integrity inevitably include the role of AI detection software. There are a number of tools in this space, but for most UK universities and colleges, Turnitin’s newly released AI detection tool will be the obvious tool to consider. The key things are:

- No AI detection tool can conclusively prove that text was written by AI.

- These tools will produce false positives.

- The tools won’t be able to differentiate between legitimate and other uses of AI writing tools.

Best practice for using such tools is still being considered and developed across our sectors, and we will aim to provide examples as these develop.

A Jisc blog post explores the concepts and considerations around AI detection in more detail, and another gives our latest recommendations.

3.2 Use in Learning and Teaching

We are seeing a wide range of ideas for how to use generative AI in learning and teaching. It’s worth remembering at this point that it is a fast-moving space and many of the tools are still under development or at the beta stage. Whilst exploration makes a lot of sense, it’s also worth noting that individuals shouldn’t feel the need to rush into using it in teaching – things are changing rapidly, but now is definitely the time to explore and start planning.

3.2.1 Examples of use by students

We welcome the fact that student voices have been brought into the discussion around generative AI, for example ‘Generative AI: Lifeline for students or threat to traditional assessment?’. Jisc has produced a report on the findings of student panels with around 200 students in 9 institutions, conducted in late 2023.

Examples of uses by students.

| Use | Considerations |

| To formulate ideas, for example, creating essay structures | Generative AI tools are generally effective in producing outlines as a starting point for an assignment. |

| To provide feedback on writing | Generative AI will proofread and correct text for students, in a similar way to grammar tools. It will also provide feedback on style and content. Students will need clear advice on when this should be declared. |

| As a research tool | A good understanding of the tool and its limitations is crucial here, particularly the tendency for generative AI to give misinformation. |

| Generating images to include in assignments. | The best image-generation tools come at a cost, and students need to be aware of copyright concerns. |

In section 2.3 we noted that digital inequality is a concern. For example, students who pay for ChatGPT Plus get faster, more reliable access, as well as access to the latest model, and those who pay, for example, for MidJourney image generation will get more and better images than most of the free options. At the moment there are limited options for licensing these tools institutionally, but we expect this to change, and consideration should then be given to licensing options to avoid inequality.

3.2.2 Examples of use by teaching staff

If used appropriately, generative AI has the potential to reduce staff workload, for example by assisting with tasks such as lesson plans, learning material creation, and possibly feedback. The key words here are ‘appropriately’ and ‘assisting’. In section 2.3 we noted some of the limitations of generative AI, such as incorrect information, so as things stand today, generative AI can assist by, for example, generating initial ideas, but its output should always be carefully reviewed and adapted.

Use of generative AI may be by directly using a general chat app such as ChatGPT, or maybe via an application built on top of generative AI, such as Teachermatic. In the former case in particular staff will need good prompting skills to make the most of generative AI. Jisc has produced a report on it’s Teachermatic pilots, indicating these tools do save teachers; time.

| Use | Consideration |

| Drafting ideas for lesson plans and other activities | The output may be factually incorrect or lack sound pedagogical foundations. Nonetheless, it may be a useful starting point. |

| Help with the design of quiz questions or other exercises. | Generative AI can quickly generate multiple-choice quizzes and assessment ideas, but they should be reviewed carefully as above. |

| Customising materials (simplifying language, adjusting to different reading levels, creating tailored activities for different interests) | Generally, when asked to customise material, generative AI won’t introduce new concepts, and so is less likely to introduce factually incorrect information. |

| Providing custom feedback to students. | At the moment, generative AI should not be used to mark student work, but it can be a useful tool for assisting with personalised feedback. |

The Department for Education has recently published the results of a call for evidence on the use of generative AI in education. which shows ways in which respondents are already benefitting from generative AI, alongside their concerns.

3.2.3 Examples of uses to avoid

In general, you should avoid posting any work that isn’t your own, and any personal information into ChatGPT, as it might well be used as part of the training data.

Things get a little more complex when considering tools built with ChatGPT, and it is almost certain that generative AI built into tools like Microsoft 365 will have the same data privacy protection as the rest of Microsoft 365.

| Use | Reason |

| Marking student work | There is no robust evidence of good performance, although ChatGPT will confidently do this if you ask. |

| Detecting whether work is written by AI | ChatGPT might claim it can detect whether it wrote the text, but it can’t |

| Anything involving personal information | You should never put personal information into any system that your University or College hasn’t got a proper contract in place with and made a full assessment of its data privacy policies etc. Generative AI services like ChatGPT are no exception. |

3.3 Adapting curriculum to reflect the use of AI in work and society.

We are seeing a broad acknowledgement that work will change too, but understandably limited action around this at the moment.

A Department for Education report ‘The impact of AI on UK jobs and training’ shows the occupations, sectors and areas within the UK labour market that are expected to be most impacted by AI and large language models specifically.

OpenAI undertook some earlier research on the impact of LLMs and jobs and has estimated that ‘around 80% of the U.S. workforce could have at least 10% of their work tasks affected by the introduction of LLMs, while approximately 19% of workers may see at least 50% of their tasks impacted.’ A 2021 report by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy looks more broadly at jobs affected by AI, both in terms of those likely to be automated and growth areas.

In the short term, we expect generative AI to be quickly adopted into courses where it quickly becomes the norm in the workplace. For example, visual arts make use of generative AI, and computer coding makes use of generative coding tools.

4. Regulation

Given the pace of change, regulation has struggled to keep up. In the UK, the government has published an AI white paper which aims to balance regulation and enable innovation. The paper makes explicit reference to generative AI and large language models. The US government have produced a Bill of Rights and the EU’s AI act is working its way through the European Parliament. The EU AI act classifies the use of AI in education as high risk, putting additional responsibilities on providers. The proposed UK approach will look to regulate the use of AI, rather than AI technology itself, through the work of existing regulators, against a common set of principles. As progress is made in this area we will endeavour to highlight any areas of particular concern for education. A Jisc blog post explores this in more detail.

5. Summary

Generative AI is progressing rapidly and is likely to have a significant impact on education for the foreseeable future. Keeping up with the advances is a challenge, and balancing authentic assessment and academic integrity is increasingly complex. Nonetheless, with care and an increase in staff and student knowledge, there are substantial gains to be made. This guide aims to give a broad introduction to generative AI. Much more has been written on the topic, and for those who wish to explore further, we have included a range of resources for further reading.

Keeping updated:

To keep up to date with the work of Jisc’s AI Team, join our Jisc mail list: aied@jiscmail.ac.uk.

Further Reading:

Artificial Intelligence (AI) Use in Assessments: Protecting the Integrity of Qualifications – JCQ (Updated Feb 2024)

Navigating the complexities of the artificial intelligence era in higher education – QAA (Feb 2024)

Generative AI in education: educator and expert views – DfE (Jan 2024)

Use of artificial intelligence in education delivery and assessment – UK Parliament Post Notes (January 2024)

Generative AI in education Call for Evidence: summary of responses Department For Education (Nov 2023)

Guidance for AI in Education and Research – Unesco (Sep 2023)

Reconsidering assessment for the ChatGPT era – QAA (Jul 2023)

Maintaining Quality and Standards in the ChatGPT Era: QAA Advice on the Opportunities and Challenges Posed by Generative Artificial Intelligence – QAA (May 2023)

Generative artificial intelligence in education – Department For Education (March 2023)

Selected relevant Jisc Blog Posts:

Staff and student use:

Innovative Insights: AI success stories from the community (Feb 2024)

Generative AI and How Students Are Using It (June 2023)

Generative AI: Lifeline for students or threat to traditional assessment? (April 2023)

Means. Motive, Opportunity: A Composite Narrative about Academic Misconduct (March 2023)

Institutional Policy and Practice

Licensing Options for Generative AI (Dec 2023)

Navigating Terms and Conditions of Generative AI (Sept 2023)

Considerations on wording when creating advice or policy on AI use – (Feb 2023)

Guidance on resisting restrictive AI clauses in licences – (Jun 2024)

AI Detection:

A short experiment in defeating a ChatGPT detector (Jan 2023)

AI Detection – Latest Recommendations (Sept 2023)

Bias and other ethical considerations:

Hidden Workers powering AI (March 2023)

Exploring the potential for bias in ChatGPT (Jan 2023)

Regulating the Future: AI and Governance May 2024

Using Generative AI:

Empowering Educators by Harnessing Generative AI Tools: Navigating Prompt Roles – (Jan 2024)

Debunking Myths and Harnessing Solutions: Navigating generative AI in Education (Dec 2023)

Etiquette for AI meeting note-taking services – May 2024

Change log

V1 .6 – 14 Aug 2024

- Section 2.1 Updated to reflect the fact GPT-4o is the latest model

- Section 2.4 Linked to ‘What is Open Source AI?’ blog added.

V1 .5 – 26 June 2024

- Section 2 – updated to reflect most tools now have internet access.

- Section 2.1 – Updated the differences between paid and ChatGPT is mostly now around amount of access to the latest model, plus GPT creation.

- Section 2.1 Added explanation on how to see if the ChatGPT s accessing the internet.

- Section 2.5 – Updated the section on cutoff date to note that most tools now search the web.

- Section 3.11 – Added link to Jisc’s student guidance.

- Section 3.21. – Add reference to the latest Student Perceptions of AI report.

- Section 3.22 – Added link to Teachermatic report.

- Section 4 – Add link to regulations blog post.

V1.4 – 4 March 2024

- Section 2.2 – Updated to reflect the requirement to have 300 users minimum for Copilot 365 has been removed.

- Section 2.3 – Updated to reflect the change of name from Bard to Gemini and the introduction of a paid option.

- Section 2.6 – Updated to include video generations tools as well as image.

- Section 3.3 – The latest DfE study on AI and jobs has been added.

- Further reading: Latest releases from QAA, DfE and UK Parliament added.

- Selected blog posts: Updated.

- Date ordering – further reading, selected blog posts and version history are now ordered in reverse datr order.

V1.3 – 2 Jan 2024

- References to Bing Chat changed to Microsoft Copilot as Micrsoft have renamed the product.

- Section 2.1 – Replaced text on ChatGPT plugins with text on GPTs.

- Section 2.2 Merged all content about Copilot into its own section to reflect Microsoft’s latest branding

- Section 2.2 Updated content on Microsoft Copilot to reflect pricing of Copilot 365.

- Section 2.3 Moved Google Bard into its own section 2.3 as it continues to evolve. Updated the screenshot and text to show the fact-checking feature.

- Section 2.4 Moved Claude and Llama into a section ‘2.4 Other Models’ – this was previously section 2.2.

- Section 3.2.2 Added reference to DfE call for evidence report.

- Further reading – added recent document DfE

- Blogs list updated

V1.2 – 16 Oct 2023

- References to DALLE-2 changes to just DALL-E with the release of DALL-E 3.

- Section 2.2 updated to reference Llama and Bing Chat Enterprise.

- Section 2.2 Reference to Claude and Bard being behind ChatGPT removed as they have progressed signficantly.

- Section 3 added linked to Assessment Menu

- Section 3.1.2 – added link to latest Jisc AI detection blog.

- Section 3.2.1 – added link to report on student forums.

- Section 4 – updated to reflect AIEd classed as high risk in EU Act.

- Further reading – added recent documents from QAA and Unesco.

- Blogs list – date of articles added

V1.1 – 22 May 2023

- We’ve added a table of contents.

- Section 2.1 (ChatGPT) has been updated to reflect the fact that all ChatGPT Plus users have access to plugins and web browsing.

- We’ve added a CC BY-NC-SA license

License: CC BY-NC-SA

Find out more by visiting our Artificial Intelligence page to view publications and resources, join us for events and discover what AI has to offer through our range of interactive online demos.

For regular updates from the team sign up to our mailing list.

Get in touch with the team directly at AI@jisc.ac.uk

7 replies on “A Generative AI Primer”

Re your claim it is “important to understand” that ChatGPT “works by predicting the next word given a sequence of words” – according to, as it were, the horses mouth: “ChatGPT’s responses are not solely based on predicting the next word in a sequence. The model has been trained on a wide range of text from the internet and can generate coherent and contextually relevant responses based on that training”.

While your claim can be thought accurate in the context of how the model operates (i.e. it uses autoregressive generation), surely it’s not the whole story and misses the crucial AI direction-of-travel – the integration of systems. Would an imaginary alien watch Earthlings writing text observe “they just write one word at a time”? Of course there’s lots more going on and is it the ‘lots more’ which it would be useful to be considering here?

For example, the claim that “as it stands today, ChatGPT doesn’t have access to the internet” is, as of March 2023, out-of-date given that newly released OpenAI plugins now enable ChatGPT real-time internet access (e.g. the Chrome WebChatGPT browser extension).

In short, is it helpful to infer that all ChatGPT does is ‘predict the next word’?

Thanks for the feedback. I agree integration is really important. Now plugins are available to all ChatGPT Plus users I’ll include this in the next update to the guide.

I totally agree with you John that only focusing on how AI predicts the next word doesn’t really capture the whole story. These systems are much more than that, like not only following pattern but reading millions of text to give a response which feels like natural and even human generated sometimes.

Hello, sir. This is a very informative work to read.

I believe that the current concept of AI detectors is flawed, particularly in light of a recent study from Stanford University. The research, published in April under the title “GPT Detectors are Biased Against Non-Native English Writers,” revealed that these detectors erroneously classified 61.22% of English essays penned by non-native speakers as AI-generated. Meanwhile, the rate of false positives for essays written by 8th grade students in the U.S. was close to zero, suggesting a significant bias in the detectors.

It is my understanding that companies like Turnitin utilize machine learning to differentiate between human and AI-produced texts. Given my knowledge in the field, I presume that these detectors are searching for unique linguistic characteristics found only in AI output, such as perplexity, log probability, n-gram, and so forth. However, as the Stanford research points out, non-native speakers tend to have lower perplexity in their writing. This assertion has been further verified by their research assessing the perplexity of around 1,500 ML conference papers authored by scholars residing in non-English speaking countries.

To further validate this, I conducted a personal experiment using Turnitin’s AI detector, courtesy of some connections I have at universities in New Zealand. When I ran a 1999 educational essay that aimed to teach ESL students- written in simple English with low perplexity – through the detector, Turnitin classified it as 100% AI-generated. I also experimented by transforming the bullet points from my PowerPoint slides into an essay, merely adding some conjunctions. Surprisingly, Turnitin classified this text as 40% AI-generated. This is likely because the content is technical and exhibits low perplexity, as it simply conveys factual information (advantages/disadvantages and definitions).

Subsequently, I used GPT-4 to generate five essays based on my course materials from this semester, asking GPT-4 to rewrite them in the tone of the Financial Times, The Economist magazine, and McKinsey reports. Astonishingly, none of the essays was identified as AI-generated. I believe the high perplexity, lexical richness, and writing quality of these AI-generated essays (with extra prompts )are superior to what 95% of British writers can achieve.

I surmise that machine learning classifiers can only effectively separate human text from AI-generated text under default conditions. Consequently, they unintentionally penalize non-native speakers whose writing tends to have lower perplexity. I understand that staff members in higher education are in a panic. However, these so-called detectors, along with any policies that ban generative AI, can be compared to the Locomotive Act of 19th-century UK. This Act restricted the speed of cars to protect the interests of horse-drawn carriage operators. In retrospect, it seems almost comical.

It’s good for Study

its so informative work to read and good for the study.

I like this blog that how it is not just about explaining tech. It keeps up with the fast evolving AI and balances the blog with the pros and cons of using AI tools. It’s a great for anyone wanting to know how to use AI (responsibly). I think the takeaway is to adapt using AI while still maintaining academic integrity.